© 2025 Peter N. M. Hansteen

On December 12 2027, it's already too late. The day before, the European Union Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) will have fully entered into force.

On December 11 2027, the Cyber Resilience Act is fully in force in the European Union member states and associated countries and territories.

From that date onward, suppliers of any "product with digital elements" are required to present those products along with a full overview and insight into all components and dependencies that went into making that product.

Unless, of course, you are a supplier that is fine with being considered at best second rate, or even being ineligible for lucrative contracts. Selling product that has not qualified for the CE mark for its product category will simply not do.

The European timeline for phased implementation of the CRA is outlined here, among other places.

Even if you are on the other side of the pond, you're not out of the woods. But more on that later.

Note: This piece is also available

without trackers but

classic formatting only

here.

Upping Your Engineering Game

For individual developers, the question becomes something more along the lines of

"Do you know what your code does?", or even

"Do you know everything your code does?".

To put it bluntly, whether you answer to either of these is a clear yes or no determines whether you are just a coder or an engineer who codes.

The purpose of this session is to help you move towards becoming the latter. To start you upping your engineering game.

To set the stage for what real engineers (should) do and to keep focus on the importance of doing things right, the anecdote of the Canadian engineers' iron ring is a useful reference.

This all sounds a bit harsh, I know. So we will go a little softer at first, much like I did in my earlier article No Project Is an Island: Why You Need SBOMs and Dependency Management.

And yes, some of this will sound familiar if you have taken in that piece or participated in the live sessions based on the text.

Dear Developer, do you know what your code does?

So let's ask the question,

Dear developer, do you know what your code does?

Your answer is likely to be along the lines of

Sure, I wrote it all. I know what it does.

Unless you vibe coded the thing, that is. But let's leave that particular set of circumstances for another time.

The answer I wrote it all. I know what it does is, however, unlikely to be totally accurate. Unless you are doing extremely low level stuff and your code speaks directly to the hardware, your code more likely than not also pulls in and utilizes dependencies such as system calls and library functions that provide the foundation of functionality that makes the code you wrote work.

Knowing your dependencies and what role they plain in making your code work is a significant part of delivering proper quality. More on that later. First, we turn to a little history of software.

Just a Bit of Typing

Software is a relatively recent phenomenon. For a long time, you could credibly say most of its existence, software was poorly understood by society and industry at large.

There was a time -- and I am old enough to remember that time -- when software was considered a minor, somewhat irritating but necessary, component in IT deliveries.

On the more extreme end of things, you would occasionally hear that software was not at all important, literally just a bit of typing.

All the while it was ever more clear to developers and practitioners that the software was what made all that expensive hardware useful. But software was all ephemereal to most and in almost all cases the source code was secret, and the customer was expected to just accept whatever came you way as-is.

That perception changed over time, and during recent decades it is no longer in doubt that the software industry is just that, an industry in its own right.

But Then Suddenly Software Turned Important

Then, as some of us still remember, the Internet happened.

Few people realized it at the time, but this was the time in history when two important things happened at roughly the same time.

For one, it became obvious to developers at least that the infrastructure we all have come to rely upon owes its strength and resilience to the fact that it consists mainly of software that was built on standards built on rough consensus and working code, code that was open source.

The other thing was that software faced the full force of the entire world banging away at their keyboards.

Some of those keyboards were operated by people who intended to do bad things.

And eventually, bad things started happening.

Over the years, eventually enough episodes piled up that software security, sometimes discussed under other labels, started becoming an issue.

During the twenty-tens and -teens, we had several incidents where software bugs were tickled enough to lead to costly and embarrasing episodes. Some of these episodes were grave enough that the powers that be (the kind wearing suits) discovered that software was indeed something they needed to care about.

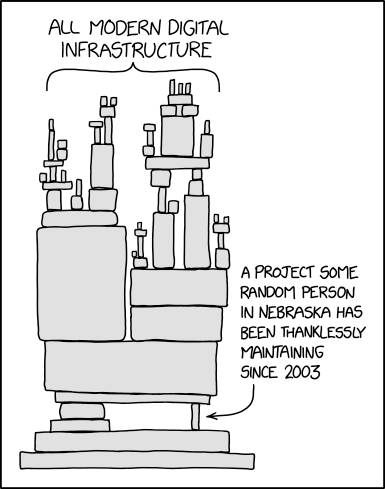

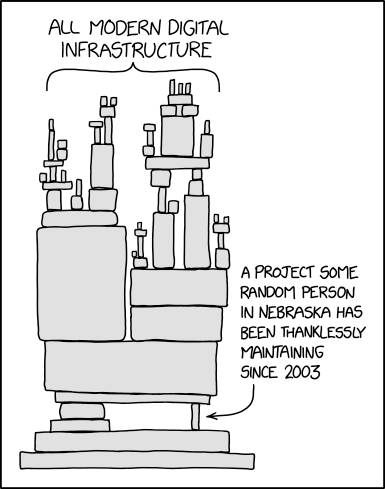

These episodes spurred several things, one being memes like

(XKCD #2347, please also read the explainer), which lead to the common belief that supply chain management and the subtopic dependency management is mainly a problem that concerns open source software.

This assertion is simply not true, in that no project is an island.

Whether you let others see the code you wrote or not, the software does not exist in isolation.

The XKCD comic struck a chord with open source developers, who at the time were a lot more in tune with the world of software dependencies than most other people.

Dependencies Became A Thing

There were several high profile and scary security incidents during the twenty-tens and twenty-teens. Some were due to exploitable and exploited bugs in open source code and dependencies, such as the log4shell incident involving a very popular logging library. This incident served to make it clear to C-level executives that dependencies were indeed a thing, and that their infrastructure was to a large extent made up of open source software.

At roughly the same time, the SUNBURST supply chain incident, which involved a popular piece of proprietary network management software that had been backdoored, demonstrated that even when the source code is kept secret, that is not sufficient protection against skilled adversaries.

These and other grave incidents made supply chain security an important new addition to our software security vocabulary.

No Project Is an Island

As I mentioned earlier, no project is an island.

Whether you let others see the code you wrote or not, the software does not exist in isolation.

Summing up so far,

-

We write software

-

Which depends on other software

-

Which interacts with other software

-

Which again interacts with other components (hardware, humans)

-

To run important stuff

-

Nothing exists in actual isolation – No project is an island

So what we do is important. What do we do about that?

Learn From Those Who Build Important Things

One way to handle the situation is to look at what other people who build important things do.

In other fields, the term Bill of Materials, or BOM for short, is a familiar term. The Bill of Materials is a document or set of documents that lists all component parts of a delivery.

This is the kind of document that becomes crucial in contexts where the procuring organization is geared toward accounting for everything and auditing when the supplier least expects it.

One such context could be when your organization has landed a contract to supply a backhoe, an armored personnel carrier or even a ship, and the contract requires you to specify component materials used, down to the nuts and bolts level.

For an example of the scale of things we are talking about, consider this ultra high level view of an item that was delivered to the UK Royal Navy, one aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth:

Your delivery would not be considered complete without the Bill of Materials or Manifest, even for a thing this size.

In practice, the BOM for the HMS QE and similar-sized projects would be a collection of BOMs with specifications for each of the multitude of component deliveries that make up the whole. Each supplier would be required to come up with a Bill of Materials for their delivery.

For physical deliveries to organizations of some stature, a Bill of Materials has been a standard part of the process across industries as an important part of quality assurance and a fundamental part of maintenance processes.

Software, on the other hand, has traditionally not been subject to that kind of scrutiny.

What Do Engineers Do?

In other fields of engineering, the process runs roughly like this:

You design your product, make detailed plans and descriptions of how to build the thing.

While planning and building, you keep track of all parts and components.

A Bill of Materials (BOM) for a pump that could well be a part of the HMS Queen Elizabeth could look like

Your plans and design documents will likely undergo changes during product development and assembly.

For each delivery, you create a Bill of Materials that is a required and essential part of the delivery.

The Bill of Materials (BOM) lists all component parts, to the detail level required for running maintenance.

The BOM typically also references and serves as reference for maintenance documentation.

As an aside, it is likely worth noting that the US Department of Defense's need for structured text markup in processing inventory information such as bills of materials was one of the more important drivers, albeit not the only one, behind the creation of SGML, the direct precursor to HTML and XML.

Again, for a long time, this kind of engineering practice was not seen as a requirement for software deliveries.

Libre Software Has Package Management Already

Handling dependencies in software is not a new thing. You probably poke around for dependencies yourself when you start looking into a new project.

You will start looking into the source code files in your project, any libraries or tools needed to build the thing would be nice-to-knows. Once you have the thing built, it becomes interesting to know what other things -- libraries, suites of utilities, services that are required to be running or other software frameworks of any kind -- that are required in order to have the thing run.

So basically, any item your code would need comes out as a dependency, and you will find that your code has both build time and run time dependencies.

Those terms will be quite familiar to users and the developers of the package manager systems for the various open source operating systems. The very same items you would recognize from a listing of package dependencies in a package management tool will turn up in our Software Bill of Materials too. Depending on the specific tool and options you use, the SBOM could contain additional information that may not be entirely relevant in a package manager context.

Under any circumstances, with package systems in place, and even vulnerability scanners available to scan for unsecure code at rest or while running, the free and open source software communities were in fact well positioned for the legal requirements when they hit. Even more, the lessons learned from package management came in quite useful in meeting and satisfying the updated requirements.

Every free operating system, and in fact most modern-ish programming languages come with a package system to install software and to track and handle the web of depenencies. You are supposed to use the corresponding package manager for the bulk of maintenance tasks.

So when the security relevant incidents hit, the open source world was fairly well stocked with code that did almost all the things that were needed for producing what became known as Software Bill of Materials, or SBOM for short.

Introducing: A Software Bill of Materials (SBOM)

So what would a Software Bill of Materials even look like?

Obviously nuts and bolts would not be involved, but items such as the source code files in your project, any libraries or tools needed to build the thing would be nice-to-knows. And once you have the thing built, it becomes interesting to know what other things -- libraries, suites of utilities, services that are required to be running or other software frameworks of any kind -- that are required in order to have the thing run.

The information is there in our code, and with development tools and code scanners a developer is well placed to poke around.

The next challenge it to take that information and present it in a way that conforms with the legal specification and is presented in a way that is usable for stakeholders that are not developers.

In addition to module or package names and versions, the expected SBOM product will typically include information on any identified security problems such as CVEs and a specification of the licenses that apply to each of the identified dependencies.

Thanks in large measure to the open source heritage of the specifications and tools, both of the commonly used SBOM specifications (SPDX and CycloneDX) consider information on licenses used in a file or project as tagging and tracking relevant items.

The tools we describe have some measure of support for tracking and reporting on licenses in use. This can be useful for flagging licenses that may be mutually incompatible or even incompatible with your organization's business goals.

Several pieces of legislation emerged from the at times panic flavored fallout from the security incidents. Which ones are more relevant to you will become clear as we move on.

Depending on what parts of the world you care more about, the emphasis will either be on

So that's our backdrop for now.

Mainly (I think) due to coordinated lobbying by major players, both have rougly the same time frames for becoming formal requirements, with the EU Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) entering fully into force, with a CE mark scheme for digital products to be in place with the same deadline.

The name of the SBOM game is compliance with those legal requirements, and to not only generate the information -- that's the relatively easy part -- but also to present the information in a way that is understandable and actionable to stakeholders who are not themselves software developers.

We're Real Engineers Now, Sparky! We Have Tools

As I hinted at earlier, there are tools available for all of this. If you want to go on and explore for yourself, I would recommend going to the awesome-sbom site, which offers a curated collection of SBOM resources and tools hosted as a Github repo.

There are a large number of tools available, with varying feature sets. In addition to the free tools you find via that collection, several tool suites exist that are exclusively commercial or with free trial or reduced features set versions out with full features available only to paying customers.

The tool set I found the most accessible for my poking around was the combination of syft for generating SBOMs and bomber for display and presentation. The home pages for both are linked from the awesome-sbom collection.

As you can see from that page, there are several SBOM formats around, and to some extent standardization and interoperability efforts are under way. But enough of that, let's look at the actual tools in use.

Tools and How To Use Them

The tool set I found the most accessible for my poking around was the combination of syft for generating SBOMs and bomber for display and presentation. The home pages for both are linked from the awesome-sbom collection.

As you can see from that page, there are several SBOM formats around, and to some extent standardization and interoperability efforts are under way. But enough of that, let's look at the actual tools in use.

As a first step, it is instructive to point syft at the base directory of your project and see if it can tell you something you did not know already. syft supports a number of output formats, so if XML is the more readable format to you,

$ syft . -s all-layers -o cyclonedx-xml | xq

will give you pretty-printed XML (assuming you have xq installed) output of what syft found out. Do explore the various command line options for extracting various information about your project.

If you prefer JSON over XML, something like

$ syft . -s all-layers -o cyclonedx-json | jq

will give you readable JSON of the same information. Again, there are a number of options to explore.

If you want an html report with known vulnerabilities

$ syft . -o cyclonedx-json | bomber scan --provider ossindex --output=html

Note: For this particular command to work, you also need to supply provider login credentials (available with free registration), see the Bomber provider documentation.

Your SBOM, The Build Artifact

When you have explored a bit, you may want to look into how you incorporate these tools in your project and make the SBOM a build artifact.

The bomber documentation has this example suggestion for inclusion in a CI/CD pipeline:

# Make sure you include the - character at the end of the command.

# This triggers bomber to read from STDIN

syft packages . -o cyclonedx-json | bomber scan --provider ossindex --output json -

Note: For this particular command to work, you also need to supply provider login credentials (available with a free registration), see the Bomber provider documentation.

For your own projects you will tweak to taste, of course.

Your Tools May Already Have (Some of) This

More SBOM-savvy co-stakeholders in your project may even be capable of processing your json or xml formatted SBOMs themselves, using tools of their choice.

Your project and customer may already have chosen a different toolset, or you may find that some other SBOM generating and presentation tool set are better matches for your requirements.

It is in fact conceivable that you have SBOM-capable tools within reach in your environment already. The fairly popular images-and-sundry repository system Harbor supports automatic SBOM generation on image push by hooking in trivy for image scanning duty, should you choose to enable that feature for your Harbor hosted projects.

Track Your Dependencies On The Fly

In a real world scenario, I could imagine that non-developers would appreciate it if you supplement that line with one using the --output=html option. The HTML output provides a report that lists licenses involved before listing know vulnerabilites by severity and assigned CVE.

While I was writing this article, a colleague who had been reviewing it told me of an episode that shows that even extremely basic use of the SBOM tools can be useful. A customer had called, saying they needed a complete list of tools and dependencies involved in a project, and right away. As a first step, my colleague cd'ed in to the main directory of one of the subprojects for that customer, and issued the command

$ cdxgen .

and was rewarded with a bom.json file that listed somewhere in excess of three hundred dependencies for that relatively minor subproject alone. The customer was suitably impressed and granted my colleague a more realistic and less immediate time frame for submitting the full dependency tree.

There Is More

If you want to explore further, please dive into the resource references at the end here.

For the more Bill of Materials savvy developers who want to explore even more, it may be of interest that the OWASP and SPDX teams are working on more specialized BOM variants, including

-

OBOM (Operating system Bill of Materials)

-

SaaSBOM (Software as a Service Bill of Materials)

-

CBOM (Cryptography Bill of Materials)

-

AISBOM (Artificial Intelligence Bill of Materials)

and several more. Again, see the referenced resources at the end here and follow the breadcrumbs.

Now It's Your Turn: Get The Tools

Now it's your turn to go exploring. The first item is to get the tools installed.

If you haven't already, go to the home pages of each:

And follow the instructions on how to install for your environment.

The exact steps to install depends, of course, on your platform.

If you are running a recent Linux distribution, you more likely than not have them within reach via your package system. Failing that, or if you happen to be on macOS or a supported Linux, the command

$ brew install $toolname

where the value of toolname expands to the name of the tool you want will get you there.

There are even instructions for Microsoft systems at some of the tools' home pages.

If none of these methods work, do a git clone of the tool source code (you were going to do that anyway, right?) and follow the build instructions.

If necessary, tweak to get the thing to work. If you find you need to do something non-trivial to make the tool build and run on your system, consider submitting a pull request to the project.

Tools in Hand, Dig Into a New Project

Now that you have to tools installed, it is time to put them and your own skills to work on some actual source code.

If you have the source for a project you are already familiar with available, or a project you are interested in exploring, choose that. Otherwise, find something you're interested in on Github or somewhere else public.

Once you have a local copy of the codebase, go to that directory.

Once there, start with

$ cdxgen .

then watch the output (it may be useful to run commands like these in a script(1) session so you can look up what happened in the script file later), and act upon it.

Be prepared that there may be issues in the code that needs fixing or some dependency that you were not aware of.

Then look up the cdxgen, syft and bomber documentation to find out the following about your chosen code base:

- What is the number of dependencies for this code base? How many direct dependencies? How many indirect ones (dependencies of dependencies)?

- Does the code base itself have any known problems, reported as CVEs? How many for the dependencies?

If you are feeling a bit more ambitious, you could try checking out the tools themselves, and run the tools on those codebases:

Fetching cdxgen source code is as easy as

$ git clone git@github.com:CycloneDX/cdxgen.git

There may be some challenges ahead. If the result of your first session looks like this (an actual script session of cdxgen run on its own source), please do not let that discourage you. Those are problems to be fixed, and you are developer enough to do that, right?

for syft, the command is

$ git clone git@github.com:anchore/syft.git

and for bomber,

$ git clone git@github.com:devops-kung-fu/bomber.git

You may find other tools, via awesome-sbom or elsewhere, that fit your tastes or your projects better than those.

This is when the fun part starts.

Resources for Further Reading

Linux Foundation Training:

Automating Supply Chain Security: SBOMs and Signatures (LFEL1007) a short but information- and reference-filled introduction (free, requires registration, gives you a badge at the end)

Understanding the EU Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) (LFEL1001) Focused on the EU CRA, gives an overview with lots of useful references, nominally a 1 hour course worth taking

The Software Bill of Materials home page at NTIA is the mother ship of SBOM documentation

Browse OWASP CycloneDX for all things about the CycloneDX specification and related tools, also their CycloneDX tool center

Browse the System Package Data Exchange specification (SPDX) for all things SPDX (supported by the Linux Foundation), including copious linked reference material

awesome-sbom is a curated list of SBOM tools and resources

EU residents will want to poke around the Cyber Resilience Act site for reference

Brewing Transparency: How OWASP's TEA Is Revolutionizing Software Supply Chains is a summary of recent work on OWASP Transparency Exchange API (TEA)

SBOM buyer’s guide: 8 top software bill of materials tools to consider is a readable overview of (some) SBOM tools

Olle Johansson's FOSDEM presentations are among several good SBOM talks at that conference (search the site for more)

Peter N. M. Hansteen: Open Source in Enterprise Environments - Where Are We Now and What Is Our Way Forward? (2022, also here) has some insights on how open source software plays a crucial role in enterprise environments and elsewhere

Peter N. M. Hansteen: No Project Is an Island: Why You Need SBOMs and Dependency Management (also here)

Peter N. M. Hansteen: EU CRA: It's Later Than You Think, Time to Engineer Up! (this article) (also here)

Peter N. M. Hansteen: EU CRA: It's Later Than You Think, Time to Engineer Up! (slides)